Produced by Charles Wells Revised 2017-04-12 Introduction to this website website TOC website index blog

When you do math, you must recognize abstract patterns that occur in

This happens in high school algebra and in calculus, not just in the higher levels of abstract math.

Most of the examples in this article concern patterns in symbolic expressions rather than in geometric figures. In my experience, that is where most pattern recognition problems occur when students are beginning abstract math courses.

The product rule for differentiable functions $f$ and $g$ tells you that the derivative of $f(x)g(x)$ is \[f'(x)\,g(x)+f(x)\,g'(x)\]

You recognize that the expression ${{x}^{2}}\sin x$ fits the pattern $f(x)g(x)$ with $f(x)={{x}^{2}}$ and $g(x)=\sin x$. Therefore you know that the derivative of ${{x}^{2}}\,\sin x$ is \[2x\sin x+{{x}^{2}}\cos x\]

This example is revisited below.

The chain rule says that the derivative of a function of the form $f(g(x))$ is $f'(g(x))g'(x)$. From this you get the substitution rule for finding indefinite integrals:

\[\int{f'(g(x))g'(x)\,dx}=f(g(x))+C\]

To find $\int{2x\,\cos ({{x}^{2}})\,dx}$, you recognize that you can take $f(x)=\sin x$ and $g(x)={{x}^{2}}$ in the formula, getting \[\int{2x\,\cos ({{x}^{2}})\,dx}=\sin ({{x}^{2}})+C\] Note that in the way I wrote the integral, the functions occur in the opposite order from the pattern. That kind of thing happens a lot.

A definition generally provides a pattern that you can use to verify something fits the definition, and even more important, it can be used in proofs.

Definition: A quadratic polynomial in $x$ is an expression of the form $a{{x}^{2}}+bx+c$ with $a\neq 0$.

Some authors would just say, “A quadratic polynomial is an expression of the form $a{{x}^{2}}+bx+c$” leaving you to deduce from conventions on variables that it is a polynomial in $x$ instead of in $a$ (for example).

Note also that I have deliberately not mentioned what sorts of numbers $a$, $b$, $c$ and $x$ are. In texts for undergraduates, the authors may assume that you know they are using real numbers, but in fact the definition works for complex numbers as well.

For real numbers $x$ and $y$, the phrase "$x$ is at most $y$" means by definition $x\le y$. To understand this definition requires recognizing the pattern "$x$ is at most $y$" no matter what expressions occur in place of $x$ and $y$, as long as they evaluate to real numbers.

The quadratic formula for the solutions of an equation of the form $a{{x}^{2}}+bx+c=0$ is usually given as\[r=\frac{-b\pm \sqrt{{{b}^{2}}-4ac}}{2a}\]

If you are asked for the roots of $3{{x}^{2}}-2x-1=0$, you recognize that the polynomial on the left fits the pattern $a{{x}^{2}}+bx+c$ with

Then substituting those values in the quadratic formula gives you the roots $-1/3$ and $1$.

The quadratic formula is easy to use but it can still cause pattern recognition problems. Suppose you are asked to find the solutions of $3{{x}^{2}}-7=0$. Of course you can do this by simple algebra -- but pretend that the first thing you thought of was using the quadratic formula.

This is an example of the following useful principle:

|

Write zero cleverly. |

I suspect that most people reading this would not have had the problem with $3{{x}^{2}}-7$ that I have just described. But before you get all insulted, remember:

|

The thing about really easy examples is that they give you the point without getting you lost in some complicated stuff you don’t understand very well. |

Even college students may have trouble with the following problem (I know because I have tried it on them):

What are the solutions of the equation $a+bx+c{{x}^{2}}=0$?

The answer

\[r=\frac{-b\pm \sqrt{{{b}^{2}}-4ac}}{2a}\]

is wrong. The correct answer is

\[r=\frac{-b\pm \sqrt{{{b}^{2}}-4ac}}{2c}\]

|

When you remember a pattern with particular letters in it and an example has some of the same letters in it, make sure they match the pattern! |

One particular type of pattern recognition that comes up all the time in math is recognizing that a given expression is an instance of a substitution into a known expression.

The product rule means that the integral of \[f'(x)g(x)+f(x)g'(x)\] is $f(x)g(x)+C$. This is useful -- you can immediately determine that\[\int 2x\sin x+x^2\cos x\,dx=x^2\sin x+C\] You know that the derivative of $x^2$ is $2x$ and the derivative of $\sin x$ is $\cos x$, so the left side fits the chain rule.

This is the sort of pattern recognition that can occur after a delay, resulting in slapping your head and saying, "But that's obvious -- why didn't I see that before!?" See ratchet effect and don't feel bad. That happens to mathematicians all the time.

Pattern recognition often occurs

after you quit thinking about the problem

and then come back to it.

This particularly happens if you take time out for a short time and get some exercise, but it also occurs overnight -- even in the middle of the night. Try it!

Reverse recognition may require transforming what you are looking at. Consider \[\int 2x(\sin x+0.5x\cos x)\,dx\]

Students are sometimes baffled when a proof uses the fact that ${{2}^{n}}+{{2}^{n}}={{2}^{n+1}}$ for positive integers $n$. This requires the recognition of the patterns $x+x=2x$ and $2\cdot \,{{2}^{n}}={{2}^{n+1}}$.

Similarly ${{3}^{n}}+{{3}^{n}}+{{3}^{n}}={{3}^{n+1}}$.

This example induces the ratchet effect in many students.

The assertion

\[{{x}^{2}}+{{y}^{2}}\ge 0\ \ \ \ \ \text{(1)}\]

has as a special case

\[(-x^2-y^2)^2+(y^2-x^2)^2\ge 0\ \ \ \ \ \text{(2)}\]

which involves the substitutions $x\leftarrow -{{x}^{2}}-{{y}^{2}}$ and $y\leftarrow {{y}^{2}}-{{x}^{2}}$.

|

chunking is a psychological inverse to substitution |

|

substitute as literally as possible and then simplify |

The rule for integration by parts says that

\[\int{f(x)\,g'(x)\,dx=f(x)\,g(x)-\int{f'(x)\,g(x)\,dx}}\]

\[\begin{equation}\begin{split}\int{f(x)\,g'(x)\,dx=f(x)\,g(x)-\int{f'(x)\,g(x)\,dx}}\end{split}\end{equation}\]

Suppose you need to find $\int{\log x\,dx}$. s(In abstractmath.org, "log" means ${{\log }_{e}}$). Then we can recognize this integral as having the pattern for the left side of the parts formula with $f(x)=\log x$ and $g(x)=x$. (Then $f'(x)=\frac{1}{x}$ and $g'(x)=1$.) Therefore \[\begin{equation}\begin{split}\int{\log x}\, dx&= \int{1\cdot\log x}\, dx\\ &=x\log x-\int{x\frac{1}{x}}\, dx\\ &= x\log x-\int{1}\, dx\\ &=x\log x-x+C\end{split}\end{equation}\]

How on earth did I think to recognize $\log x$ as $1\cdot \log x$?? Well, to tell the truth because some nerdy guy (perhaps I should say some other nerdy guy) clued me in when I was taking freshman calculus. Since then I have used this device lots of times without someone telling me -- but not the first time.

This is an example of another really useful principle:

|

Write $1$ cleverly. |

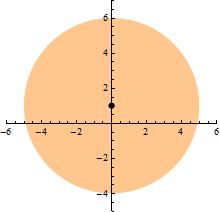

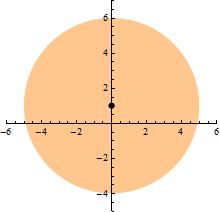

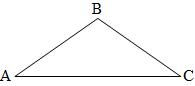

Some proofs involve recognizing that a symbolic expression or figure fits a pattern in two different ways. This is illustrated by the next two examples. I have seen students flummoxed by Example ID, and Example ISO is a proof that is supposed to have flummoxed medieval geometry students.

\[xy=e\ \ \ \ \text{and}\ \ \ \ yx=e \ \ \ \ (1)\]

In this situation, it is easy to see that $x$ has only one inverse: If $xy=e$ and $xz=e$ and $yx=e$ and $zx=e$, then \[y=ey=(zx)y=z(xy)=ze=z\]

\[x{{x}^{-1}}=e\ \ \ \text{and}\ \ \ {{x}^{-1}}x=e \ \ \ \ (2)\]

To prove the theorem, I must show that $x$ is the inverse of ${{x}^{-1}}$. Because $x^{-1}$ has only one inverse, all we have to do is prove that

\[{{x}^{-1}}x=e\ \ \ \text{and}\ \ \ x{{x}^{-1}}=e\ \ \ \ (3)\]

But (2) and (3) are equivalent! ("And" is commutative.)

This sort of double substitution occurs in geometry, too.

The point is that although triangles $ABC$ and $ACB$ are the same triangle, and sides $BC$ and $CB$ are the same line segment, the proof involves recognizing them as geometric figures in two different ways.

The triangle $ACB$ with labels is actually the same triangle as $ABC$ with labels by flipping $ABC$ over the vertical line through $B$.

This theorem is called the pons asinorum (bridge of donkeys). It became famous as the first theorem in Euclid's books that many medieval students could not understand. I conjecture that the name comes from the fact that the triangle as drawn here resembles an ancient arched bridge. These days, isosceles triangles are usually drawn taller than they are wide.

In matching a pattern you may have to insert parentheses. For example, if you substitute $x+1$ for $a$, $2y$ for $b$ and $4$ for $c$ in the expression \[{{a}^{2}}+{{b}^{2}}={{c}^{2}}\] you get \[{{(x+1)}^{2}}+4{{y}^{2}}=16\] If you did the substitution literally without editing the expression so that it had the correct meaning, you would get \[x+{{1}^{2}}+2{{y}^{2}}={{4}^{2}}\] which is not the result of performing the substitution in the expression ${{a}^{2}}+{{b}^{2}}={{c}^{2}}$.

You can easily get confused if the patterns involve a switch in the order of the variables.

Note that the calculation in the example of integration by parts to find the integral of $\log, x$ involves reversing the order of the items being substituted.

The problems with integer division mentioned in the previous section is not helped by the fact that "$|$" and "$/$" are similar but have very different syntax:

Math notation gives you no clue

which symbols are operators (used to form expressions)

and which are verbs (used to form assertions).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 License.